Elgar's Trombone

Introduction

Further exploration led me to the Royal College of Music Museum, where there were two tarnished silver 19th century trombones, identical to the one I had found in my school’s music-room cupboard at the tender age of fifteen. These RCM trombones had belonged to two of England’s finest composers: Sir Edward Elgar and Gustav Holst.

In November 2009 the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment decided to perform Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius. This prompted a revisit to the RCM museum and Jenny Nex, the Curator, granted me permission to use Elgar’s trombone for that project.

I played this instrument alongside F trumpets, piston horns and a complete section of Boosey 19th century English trombones (including a G Bass). Playing the music of Elgar on such instruments produced a unique colour that married beautifully with both soloists and choir. There was a more distinctive colour difference between the old instruments compared with modern ones, and unusually, we didn't get the customary conductor’s complaint: “Brass, you are too loud!”

It was from this experience that I felt a need to explore further the world of the 19th century English trombone and the music that was written for it. What better way than through the stories and music of Elgar and Holst and their exposure to playing such an instrument?

When researching the music for this project, I wanted to rely on one of Elgar’s greatest strengths: his ability to write very beautiful melodies. Unfortunately, most were written for violin, cello, piano, voice and full orchestra, but certainly not for the trombone. I explored the works of his contemporaries and also found equally stunning tunes, well-suited to the trombone but again not written expressly for it. As I felt the melodic quality of the music was a priority, I decided to arrange some of this early 20th century repertoire and use it as a showcase for the instrument that Elgar himself played.

Sue Addison

Elgar the Trombonist

Cartoon by Elgar sent to Jaeger.

On one occasion he got up and fetched a trombone that was standing in a corner and began trying to play passages in the score. He didn’t do it very well and often played a note higher or lower than the one he wanted, in fact anywhere but in the

“middle of the note”; and as he swore every time that happened I got into such a state of hysterics that I didn’t know what to do. Then he turned on me: “How can you expect me to play this dodgasted thing if you laugh?”

I went out of the room as quickly as I could and sat on the stairs, clinging to the banisters till the pain eased, but it was no good. I couldn’t stop there as he went on making comic noises, so I went downstairs out of earshot for a bit.

Elgar’s teacher was Arthur Edward Lettington who was a member of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra. He was among the players of the “King’s Band” at the Coronation of Edward VII at Westminster Abbey on the 9th August 1902. W.H. Reed, a personal friend of Mr. Lettington’s and leader of the LSO, referred to him in 1912 in his autobiography:

A little later on in 1904... it was about the time he was writing Falstaff, just after the Second Symphony and the Violin Concerto, that Elgar took trombone lessons with Mr Lettington, bass trombone in the London Symphony Orchestra at the time, and it may be that Mr Lettington introduced him to use the tenor clef for his first and second trombones in Falstaff, though years later, in 1932, he again wrote for all three in the bass clef in the Nursery Suite.

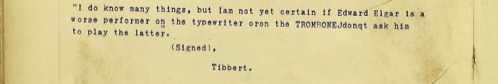

The bottom of a joke letter written by Elgar in the guise of made-up persons, testifying to his typewriting and trombone-playing abilities.

The Fate of the Trombone

In an article printed in the Red Triangle Magazine dated November 1918 can be found the following quote:

“The donkey cart has just brought another double bass,” said a member of staff.

“So I hear,” said the secretary, “did it bring anything else?”

“It brought this,” was the reply, and the speaker pointed to a trombone. A letter lay beside it.

‘This trombone’ it read, ‘has clinging to it happy memories of my youthful music-making. I meant to keep it. But why should I keep it for sentiment when the “boys” can put it to use?"

The signature on the letter was “Edward Elgar.”

I have read through all the minutes documented in the archives at the University of Birmingham and there is no further record to suggest that the instrument ended up on the frontline, or who played it. It disappeared from 1918–1934, and it wasn’t until the announcement of Sir Edward Elgar’s death that the musicologist Percy Scholes put an advertisement in the Daily Express (24th March 1934) stating the need for Elgar’s trombone to be found and placed in some national museum. The Ealing Branch of the YMCA came forward and presented it as a gift to the Royal College of Music in the same year.

Unfortunately the inscription engraved on the bell by the authorities at that time (see below) could lead one to believe that Elgar played the instrument as a boy, but there is no evidence to support this. I can only imagine that someone misrepresented the phrase “...happy memories of my youthful music-making.”

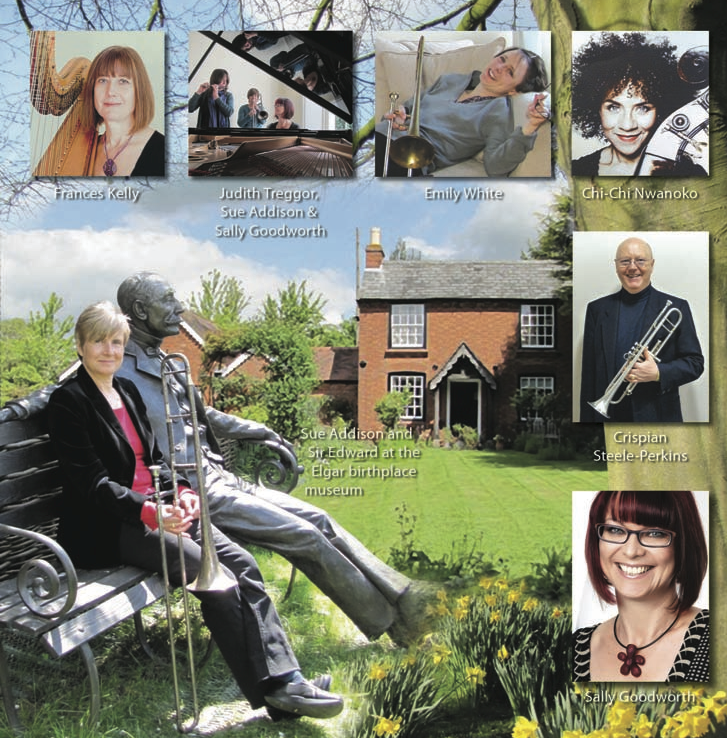

Artists

End Note

Many people seem to think that a great creative artist must be more or less eccentric and a law unto himself. To them probably the most remarkable thing about Elgar, apart from his musical ability, is that he was sane and normal. He liked and enjoyed ordinary things–fun and nonsense, games and sports, birds and beasts–and was temperate and controlled. He loved his wife and he loved his home. I have always thought that his sanity is reflected in his music which, however original, is never freakish and never morbid.

Elgar described his inspiration in these terms:

My idea is that there is music in the air, music all around us, the world is full of it and you simply take as much as you require.

Acknowledgements

A very special thanks to David Long, for his generosity in providing Sherbourne Manor and its wonderful piano and surroundings for a week of live-in rehearsing and recording.

Thanks also go to Jenny Nex, Curator of the Royal College of Music Instrument Museum, for entrusting me with Elgar’s trombone in order to give recitals and make this recording; and to Michael Rath of Rath Trombones for careful restoration of the instrument.

This has been a huge project to pull together, and could not have happened without the assistance of The Royal College of Music, the Elgar Birthplace Musem, The Elgar Society, the University of Birmingham and the Birmingham Conservatoire of Music. Grateful thanks to all these institutions, and to Sally Goodworth, Shelagh Thomson and Mary O’Neill.

Extracts from Mrs Richard Powell’s Memories of a Variation have been taken from the Remploy Edition of 1979. This mentions a previous edition of 1937 but gives no details of the publisher. Every effort has been made to ascertain the owner of the original copyrights. Please contact the Publishing Manager of Cala Records Ltd (see inside back cover) for any matters concerning acknowledgments.

The extract of the letter from Elgar is reproduced by courtesy of the Elgar Birthplace Museum. The cartoon on page three is used by courtesy of Jerrold Northrop Moore.